Not long ago I was writing some notes for The Constellation of Man about certain self-deceits of abstract thinkers, and in particular—to put a page of discussion succinctly—why philosophers (in a broad sense) feel accomplished about verbal descriptions of the world that do not match it. Even writing about false models yields an inward sense of order, and (like scientific knowledge) some sense of control over the world or orientation within it.

Every time I make a case along these lines—about the limitations of language, or against relying on any intensive subculture & psychological type built on systematic thought (e.g. men of letters, academics, scientists, philosophers)—it is intended to be constructive, in my Nietzschean fashion. But resistant, worrisome notions do spring to mind:

- that I am going against the grain of defenses of the “life of the mind” which intellectuals tend to write today, in possibly-vain attempts to popularize it;

- that attacks on dumbed-down culture depend on endorsements of linguistic and mental prowess that I could be seen as undermining;

- that I am aiming at easy, marginalized targets—groups which have included or still include myself;

- that I might be read as though I’ve succumbed to the pervasive disease of self-disgust.

It’s difficult not to write in solidarity with a marginalized group that one belongs to. I am keenly aware of writing for (against?) a modern audience, a quasi-literate world, which largely rejects my kind.

By “my kind,” I don’t simply mean intellectuals in the enterprising sense.

This world barely knows what to do with a generalist, the “Renaissance man” who once would have occupied essential roles, and renders almost every deep thinker an outsider if not an outcast. This has become so normalized they do not imagine their abilities could ever be welcomed. People dislike introspection, shrug at philosophy, and dismiss challenging literature. Intellectuals have few opportunities that pseudo-intellectuals have not taken. Fakes thrive in a culture tolerant of superficiality, and selling-out. The “literary world” is replete with an embarrassment of writers who should not have bothered, inspired by third-hand moral notions from ideologues, and boring formulae for creativity. Quantity proliferates while investing in quality seems pointless or quixotic. “Philosophers” are either dead, academic, or popularizers recycling old ideas. (Admittedly the sometimes-aligned categories of psychologists and scientists are more popular categories and aspirations, but these oftener refer to technical professions that don’t have much to do with being a “thinker.”)

My kind are infrequently persecuted today, but only because we are hardly seen. We feel as if we are, but much more to the point, we are ignored when we crusade, and superfluous in our hiding places.

What I do, and what I stand for has no purchase in a world that seeks not the transformative power of understanding, but nodding in agreement, and vituperative argument. The outspoken detest nuance and repel curiosity. Elitist snobs, smug about nothing more accomplished than a highfalutin philistinism, look down on the coarse folk who are proud to spite them with the lowbrow kind.

Everywhere we witness the unspiritual work of the uncreative, uninterested in profound human experience, and worse, contemptuous of it. Humanism no longer means anything useful. It is a world which has left behind both the apolitical (or antipolitical) values of culture, and the virtues of Man.

So I feel that I should stand up for philosophy, for genuine intellectuals, for long thoughts and real books. I am very sympathetic.

But I see it as part of my task to sincerely address the limitations of words and the foibles of thinkers. It may have to come across as self-effacing, when I least wish to be.

Struggling to grasp and to tell discomfiting but important truths is one of the distinctive habits that sets us apart from other people—if “we” aim to be more than merely literate or articulate, and also aim to question things. Certainly the great many who believe what suits them do not relate to that habit, or appreciate it.

As far as claiming an identity, however, I think it is more important that turning that microscope toward ourselves distinguishes those of us who pursue genuine intellectual, psychological or philosophical effort from poseurs, who only retell the familiar truths they already overcame, knowing they might disturb or uproot someone else.

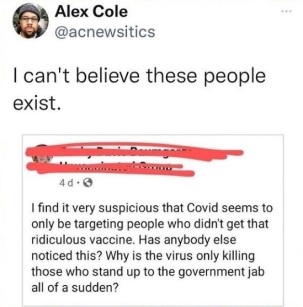

I count among these the “skeptics” who feel no duty to be skeptical of their own convictions. Those who no longer challenge their own justifications while they challenge others to reexamine theirs are more properly referred to as moralist than intellectual in any progressive or inquisitive sense.

In any case, the unexamined limitations of thinkers, and of philosophy—especially second- or third-hand ideas, in academia, journalism, and authorship of popular media—have poisoned or imperiled so much progress, there is far more at stake than being true to oneself in the tradition of thinkers with an intellectual conscience.

The Cult of Letters

Intellectuals have long wished for other people to agree with them about the value of verbal ideas in themselves. They prefer a life of ideas, so their affinity is natural. Of course they also have an interest in bringing ideas to others, and interpreting them for others, for the status and influence it brings. At the same time they have some interest in opacity, not unlike that of priests who interpret the enigmas of a mystical religion. Intellectuals do not wish for transparency about their motives, and they do not wish to have their value questioned. They are no freer of ego than anyone else, as a rule, and no more disposed to introspection.

Questions are reasonable. What is the value of books, beyond selling books? What is education for, besides enlarging the industry of education, or providing technocrats able to perpetuate a system? What can language change? When we talk about things, what are we really accomplishing? Are we really getting to the bottom of anything? Is an intellectual life more profound than, say, a visceral life, or a life spent in nature? Is “book learning” more important to self-development than say, sexuality, or traveling?

What specific and personal reasons could an intellectual have for the ideas they subscribe to, other than the neutrality, objectivity, or intelligence they prefer to presume? More importantly, what will paying attention to what they say bring to someone who does?

What is the point of philosophy or philosophers, besides their own purposes, interest, fascination, or importance? Why should others pay attention to something they write, instead of—for instance—learning an ostensibly more practical skill? Why should it hold more value than say, manufacturing a better refrigerator, shipping trade goods, or planting a nice garden?

(I believe I know the long and unflinching answers to questions of this sort, but my point is that it’s truly extraordinary not to ask them. How usual, yet how egregious of the intellectual ilk to simply feel entitled to respect from others, like an aristocrat or bureaucrat, without earning it by doing serious work and making a real contribution to life. A contribution need not be measurable, or quantifiable, or immediate, or tangible, but surely one could explain it, or demonstrate it, if it were real.)

Making a case for Art instead of mere entertainment bears a similar burden of proof. Art diverts personal, temporal, material, and financial resources to be lavished upon its creation, and appreciation. Art is difficult, and it makes demands. Why a troublesome mental exercise instead of a diverting story? If the mental exercise is our diverting story, we think the answer is straightforward: art, surely, should speak for itself. The artist, whose creative experience is so profound, also thinks art should not need justification, as does the aesthete. But art does not speak for itself, except to those who are already convinced by their emotion and perception.

We deceive ourselves to think that—unearned—a civilizational value like self-knowledge, or the means of the written word, speaks to those who have never known its worth personally. Justification is precisely what we must provide, if we wish to make the extraordinary case that our business, our cause, our purpose, our great project should become the business of others who presently see a perplexing waste where we recognize a necessary investment. Why should others who see an abstraction where we feel much more, join us and devote themselves to furthering its reality in some way, or support us in our work to do so?

It’s tempting, sometimes necessary, to write defenses of what is being lost. What is really called for is not idealization of these things, or of the types of people who are already persuaded by them, but first: transparency in admitting why certain people might already be won over. Sometimes, they have a liking as instinctive as any other. Unflatteringly, they might have motives as aggrandizing or indulgent as any.

Second, and only after establishing credibility with the first: communication which deepens the shallow appreciation others have. Demonstrate the value of a life, if you wish others to adopt any part of it.

If a philosopher is drawn to philosophize partly for the benefit of setting his mind in order—comparable to what practicing yoga does for others—this makes a surprising argument for learning to think in just such an ordered (precise, careful, or systematic) way—if not specifically as a philosopher, then as a critical thinker, perhaps under the label of a scientist.

(I remember hearing this sort of argument made for studying classical languages, back in prep school—in the traditional, philological manner, with formal grammar and linguistics. I thought it strange at the time, but in retrospect, it makes excellent sense to me. Even as the specifics of a Latin and Greek education fell into disuse in my memory, habits of explicit mental order continued to be useful.)

Another illustration: a poet is almost certainly a pretentious thing to be, a verbose and vestigial role about as vital as an appendix, to anyone who has not written poetry because they felt it—or else, heard their sense of life echoed in poetry, having understood that imagery and cadence are the birthrights of a tongue.

We are used to disingenuously speaking of the social good, instead of the personal good, when the personal good can be an easier case to make and a more persuasive one. Societal virtues from “creativity” to “learning” remain abstract, until they can be personally appreciated. That is true even if consequences of eroding a virtue—for enough people to fail to express it personally—are grave. The utilitarian argument for a virtue is weak by itself. Imagine the position of defending “romance” that way to someone who had never felt it!

A brief digression: conversely, what if the consequences for neglect are not dire? The same exercise of demonstration—of including others to understand, or at least participate in what they are missing—indicates selective importance when it is not persuasive; people find out what they are missing, and it is not much.

Narrow intellectual interests that have been claimed, justified, even trumpeted as “socially relevant” turn out to have relevance to a very few who articulate them. These have marginal importance to “society,” as this is comprised of nothing other than actual people. Personal knowledge obtained from familiarity is a valid microcosm of consequence, albeit incomplete.

Like an aesthetic that appeals to a certain type, some subjects are trivial and dispensable to anyone else who gets to know them. They aren’t merely specialized areas of expertise that are useful to others indirectly, like engineering—a fact which familiarity with the subject would reveal. They turn out to be extrinsic to civilizational needs, as well as the marrow of human pursuits.

(As an aside, I would argue that a case of precisely this is ongoing, as ideas about “identity” originating in academic cul-de-sacs reach a larger audience, third-hand, through mass-produced fiction with a see-through agenda, and internet media. To be lectured tastes like bitter medicine, particularly without the coating of a good story, or a dramatic proposal. But more than this, a wider audience finds these ideas themselves inapplicable, vacuous, or tiresome instead of liberating or redemptive [like any resounding myth]. The interested group may have expected to acquire importance like the medical experts the public willingly deputizes at great expense to cure disease; we need not understand the details to believe that specialists studying them conduct valuable work. Promulgators of identity politics may have hoped to awaken others to an ethic, or hoped to inspire existential discovery, much as promoters of class theory had hoped. Instead, today their diagnostics of “identity” are revealed to be—for most intents and purposes—neither remedial for social problems, nor inspiring to most individuals, as interesting as they seem to a self-appointed group.)

I see it as my task to show many of the virtues I wish were more prevalent, so they can be believed. I see it as my task to lay bare faults that can be remedied only if we are pointed to them, but also to concretize these things—like “the life of the mind”—that devotees want others to see as magical, too, and describe with an air of gnosis, things which more often appear unreal to others and therefore unconvincing.

If we claim anything as a pure good—as people have done with comprehensive knowledge, subversive knowledge, and every approach to “truth”—people will know this for a lie. They will suspect we are being vague about why it is a good at all, because it is not good for much. They can even dispute its substance completely, except as our favorite form of frippery, which they have no need of. Perfection is unconvincing.

Without acknowledging that there presently exists great skepticism, and perhaps for good reasons, toward many of the expensive, strange, troublesome, sometimes self-sacrificial values that generalists, artists, outsiders, crusaders, mavericks, psychologists, intellectuals, thinkers and philosophers take for granted, we will never convince those who subscribe to specialized, bourgeois, materialistic, literal, popular, and conventional values today that they are deprived—nor (as I believe) that they are taking terrible risks with the future, and with things that matter to everybody. This is a case we can make only by earning the right to make it.

We should be willing to say “Perhaps they are right!” and even dare to say, “Maybe what I am doing is useless, or unimportant,” or at least wonder in what particular ways that might be so. There is no other way but to admit the possibility, and entertain it provisionally, so that the impractical can be shown to be practical—or so that it can be made so by developing it with greater substance, relevance, and honesty than before. Unproductive occupation, and trivial preoccupations can be abandoned, so that other lines can be taken up with energy.

These are the gifts of criticism. Centuries of cloistered assurance and praise have enfeebled the life of the mind, gutted the profession of the philosopher (except for those who followed Nietzsche, who reformed by asking the hard questions), and debased literature and intellectualism.

With all our technology, we are scrabbling for the stuff to repair civilization, mixing one mortar after another that will not hold. I would not ignore those who do not trust thinkers (as they know them), or value thinking deeply. I would listen to people who are not satisfied by ideas today sooner than I would blame them.

We should keep asking the same questions they do, on the face of it: “What good is it?” And good for whom, and good for what?

This is a radical impulse, instinctively resisted by those who are invested in depth and complication. Nevertheless, it is a good one intellectuals neglect. They will not hear it. Their habitual inner rejoinder is always, “if only you knew the depth and complication I do!”

The doubts and questions seem superficial—and they are—when (as the intellectual knows) they are challenges that come from simplicity, from unfamiliarity with intellectualism, and ignorance of that “depth and complication.”

In fact, it is the intellectual who can take the doubts and questions deeper, enrich them, and fulfill their exploration, which is so essential; a life of study, and working with ideas, is essential to knowing how to question itself properly, and not just essential for instructing others. But insofar as carrying on with these simple, pragmatic questions appears to be a quest to destroy oneself—to undermine a reason for being, to unmask triviality, to obsolete oneself—the intellectual refuses to take it up seriously. The intellectual calls those simplistic questions.

In fact, so many intellectuals resist explaining themselves as clearly as they can—preferring the obfuscation of jargon, and to write in academic formats—that it suggests genuine, existential doubts about what and how much they really have to say, and even their professions. Do they know what they are good for, and why anyone else should care? Confidence does not always mean a reason to feel confident, and of course many poor amateurs with ideas convert credentials into popular books or platforms. But the lack of confidence to speak clearly and speak out oftentimes suggests the construction of elaborate and preposterous facades to distract—from what? Perhaps, from foundations that no one looks forward to testing. Perhaps from a Potemkin village, or a show city for no one to really live in. Perhaps also a construction project that is continually built, ripped down, and rebuilt so that its architects and laborers have eternal work.

Those who work, in some sense, to build civilization would not be afraid to say so, or at least to take pride in their part of it. Otherwise, people will rightly suspect this is not their business, at all. Creators who have a promise to fulfill, and a humanistic reason to act, would not be reluctant to explain how and why.